Norm Saunders: The Book & Cards!

By Kurt Kuersteiner ©2009 Monsterwax Monster Trading Cards for The Wrapper MagazineCivil War News, Battle, Mars Attacks, Ugly Stickers, Wacky Packages ... If you collect art cards from Topps, you can't help but notice the best of the best all had one thing in common: the artwork of Norman Saunders. Collectors of vintage pulp magazines notice the same thing. The newsstands before and after WW2 were dominated with his lurid covers. The artwork seemed to jump off the page and demand that pedestrians pause to peak inside. It cost just 25 cents to own his art when he first started drawing for Capt. Billy's Whiz Bang in the 1920s, and it remained that cheap in his retirement years as Wacky Packs sold for the same amount in the 1980s.

Saunders published over 4,000 illustrations, a mind blowing record for any artist, but it's especially impressive when you consider the superior quality of each piece. This wasn't by accident. Saunders intentionally made certain every assignment was as good as he could make it. He warned other painters, "If they only have $65, never do a $65 job! You'll ruin your reputation. Always do your best work and be proud of it!"

One artist who took his advice to heart was his own son, David Saunders. David was Norm's youngest child, and now he's an accomplished painter and sculptor (www.davidsaunders.biz). He remembers growing up in the 1960s while his father toiled away in his upstairs studio, painting various card sets for Topps. (Read David's memories of the Superman In The Jungle series in Wrapper #212). In the 1970s, Norm began to reflect on his life's work, and feared it was all forgotten as the magazines and card sets were thrown away after a few weeks of use. He confided with David about wanting to assemble a retrospective of his wide ranging work in book form. He insisted such a book be published after his death. David attempted to do this when Norm died twenty years ago, but he didn't have the support or resources to make it happen. When his mother died in 2006, he used his entire inheritance to finance Norman Saunders, a 368 page hard bound coffee table book. It's stuffed with Norm's incredible works, and includes a chronological biography of Norm from birth to full artistic bloom. There are photos of him and various family members (often in costume) posing for paintings that would later become famous magazine covers or classic trading cards. Best of all, there are hundreds of detailed reproductions of the finished paintings themselves. This is the closest thing we have to a Norm Saunders National Museum, and it's certainly worth the cost of admission.

Despite his incredible talent, most of Norm's life was not financially successful. He was born the illegitimate son of a poor farm couple on New Years Day in 1907. At age three, he was fighting with another child and struck in his right eye by a red hot poker from the fire place. The wound became infected and got progressively worse until he was given up for dead by both parents. They made one last effort by handing the dying child over (wrapped in a blanket with a note pinned on it) to a railroad employee to drop off at an open hospital ward in Minneapolis. Months later, the parents were surprised and delighted to discover their son was not only alive, but with full eyesight. The boy became interested in calendar art. One day, he noticed that the Saturday Evening Post cover was painted by Norman Rockwell. He decided if that Norman could be an artist, so could he! He started doodling and keeping a homemade sketchbook.

At the ripe old age of 13, Norm rebelled against his parents and left home. He bummed the rails and ended up working in saloons and a Mississippi river boat as a dancer and piano player. He eventually returned home and submitted unsolicited cartoons to Capt. Billy's Whiz Bang magazine, which soon paid him for his work. He used that money to enroll in the world's largest correspondence art school at the time, The Federal Schools of Minneapolis. He graduated with the school's top honor of a full scholarship to the Chicago Art Institute. He left home again in 1927 to move to Chicago to enroll. A former instructor suggested he kill time before school by working at Fawcett Publications. Equipped with a letter of introduction and samples of his work, he visited the busy offices unannounced. He was mistaken as an employee and given a rush assignment. He took a vacant table and painted the job. When he turned it over to the editor, he was given four more to do. This went on for a week until the paychecks were being passed out and the editor realized Saunders wasn't on the staff! When confronted about it, he started to dig through his pockets for his letter of introduction, but the editor told him not to worry, he was hired! When Fall semester arrived, Saunders decided to forego his scholarship in order to keep his new job.

Saunders continued working at Fawcett when the depression hit. His large number of covers for Modern Mechanics and Mechanical Package Magazine made him their highest paid artist at the time. After signing a particularly large check, Capt. Billy Fawcett hand delivered the payment to Saunders saying, "I wanted to meet this artist who makes as much money as me!"

When Fawcett publications moved to New York in 1933, Saunders soon followed. The pulp magazines were eating into Fawcett's profits, but those magazines also needed artists. Saunders sold them covers but signed them using his middle name, "Blaine." Some of pulps to feature his work included All Detective Magazine, Mystery Adventures, Saucy Stories, Spicy Mystery, and Public Enemy. By 1937, Saunders branched out into other genres so that he wouldn't become pigeonholed into one type of art. A sample of his titles included All Western Magazine, Wild West Weekly, Jungle Stories, Fight Stories, Sport Story Magazine, Football Action, Love Romances, Variety Novels, Sky Devils, Marvel Science Stories, Eerie Mysteries, and Crime Busters.

By 1939, Saunders had a good, solid income. He expanded into the more lucrative slick magazines (which had regular subscribers and advertisers), including Liberty, Click, Spot, Male, Stag, and Woman's Day. To improve his skills even more, he enrolled in the Grand Central School of Art to study with Harvey Dunn. Saunders continued working while studying with Dunn, who, on occasion, would bring new magazines to class to critique. While extolling the praises of one cover in particular, Dunn realized it was the work of Saunders. He slapped his student on the back and said, "You're too damned good to hang around here pretending to be a pupil! If you stay here any longer, you'll start to paint like me, and I don't need any disciples! So get out of here and get to work!" And that's exactly what he did.

Unfortunately, the war came along and Saunders was drafted. He dutifully married his girlfriend, Marion Mclean, so that if he were killed, she would be provided for. He guarded German POWs in transit to different camps, and later, was reassigned to camouflage fuel depots in China. He continued drawing and sketching all the while. When the war finally ended, it was not the happiest of homecomings for Sgt. Saunders. He received a note that his wife had committed suicide. It turned out she had been living with another man in Saunders' apartment on his government stipend and couldn't bare the shame of discovery upon his return. The tragedy haunted Saunders for the rest of his life, all the more since he would have given the new couple his blessing. About the same time, he learned his father had suffered a heart attack and wasn't expected to recover. Fortunately, he did manage to get home in late 1945, to see him before his dad died.

In September, 1946, Saunders married Ellene Eleonore. In 1951, they bought a NYC townhouse and began a family. The family grew to four: Jimmy, Blaine, Zina, and David. (Zina Saunders is also a renowned artist. She did the entire Native Americans card set for Bon Air.) The postwar market wasn't as lucrative for artists as it had been before the conflict. To compensate and provide for his large family, Saunders produced more and more.

In the 1950s, Saunders painted a slew of classic comic book covers, including Hopalong Cassidy, Tom Mix, Kid Cowboy, G.I. Joe, Explorer Joe, Speed Smith The Hot Rod King, Baseball Thrills, Wild Boy, Ellery Queen, Crime Clinic, Another World, Space Patrol, Worlds of Fear, and Classics Illustrated. He painted 95 comic covers in total. When the 1954 Comics Code cut the bloody heart out of comics, Saunders continued to paint explosive covers for paperback books. He completed 105 of those, including the first paperback appearance of Conan the Barbarian and all five of the very collectible Mysterious Traveler covers (based on the popular radio horror series).

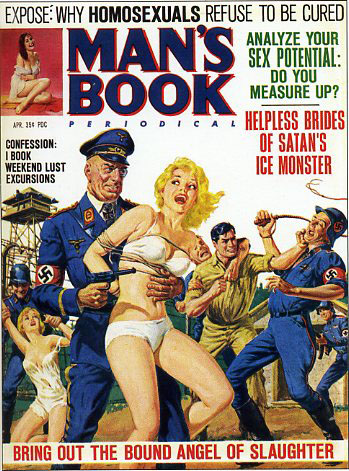

Saunders would return to paperback covers in the 1960s when he worked for a former colleague who produced erotic paperback covers. The man was supposedly backed by organized crime and eventually became a well known pornography magnate. It wasn't Saunders' first foray into erotic subjects, however. He started painting men's adventure magazines in the 1950s as well, and by the 1960s, they had become pretty, well, sleazy. (Not that there's anything wrong with Nazi officers dangling snakes and spiders over screaming women captives in ripped undergarments!) The more outrageous they got, the less Saunders signed them, but the artistic freedom to go beyond the usual line was liberating and fun for the artist. As he later joked to his son, "I only got interested in art in the first place because I wanted to look at naked ladies!" The magazines he painted for included Man's Book, Climax, Male, New Man, Man's Story, and my favorite unintentionally funny title, Men Today !

Trading card fans will be pleased to see 80 pages devoted to Saunders' non-sports work. He was hired by Topps in 1961 to be one of four artists to paint Civil War News. Each was to do 22 pieces. When Saunders submitted his work to the art department director, Woody Gelman exclaimed, "I can see every brick!" He then handed the other paintings to Saunders and said, "See what you can do to bring these up to your standards!" Saunders sat down at a desk and retouched the other 66 pieces in one day.

The trading card section is a treasure trove of images and information. For instance, did you know that Saunders invented and designed the Nutty Initials (1967) series? Many assume it was Basil Wolverton, who also freelanced with Topps, but it wasn't. Wolverton alienated himself from Topps when he tried to retain copyright control of the Ugly Stickers he did for Topps in 1965. Topps paid him off for the twelve he had painted and then fired him. It was Saunders and Wally Wood who did the remaining images in that set. Later on, he suggested the Nutty Initials idea and they let him have free reign with it.

Another issue this book resolves is that regarding the legitimacy of the 13 revised Mars Attacks cards. They were issued in 1984 by Steve Kiviat of Rosem Enterprises and were called Mars Attacks- The Unpublished Version. They show less violent versions of cards #3, 6, 8, 11, 15, 17, 19, 21, 29, 30, 32, 36, and 38. Chris Benjamin's guide was uncertain if they were real, since their exact origin couldn't be documented. But according to the new book, "Topps hired Saunders to paint amended versions of the most shocking cards. [He was] amused by the hypocrisy of selling amended 'indecent' cards under a fake company name." (Topps changed their copyright notice to "Bubbles, Inc." to dodge any controversy that the cards might cause.)

To make certain David wasn't relying on an unreliable third party for his card censorship story, I contacted him to ask if he had any personal knowledge that they were definitely real. His response: "My father did paint them. I saw him doing it and I remember the entire controversial process of producing a less offensive version of certain cards. The image of the girl in bed that is being attacked by a Martian breaking through her window, was repainted to show a guy in bed, but instead of just any guy, Norm thought it was fun to make the guy a self-portrait, so that guy in bed with a mustache is a self-portrait of the fifty-five year old Norman Saunders! All thirteen images in that 'unpublished' set were painted by Norman Saunders."

The book concludes that particular controversy with this: "In the end, the lure of potential profits was not as great as Topps' fear of bad publicity for their more lucrative business of selling wholesome bubble gum and baseball cards, so the revised set was shelved and no additional printings were made." It also shows some colorful close up photos of the original revisions.

Other interesting Mars Attacks details are that David himself posed as the boy in the famous Destroying A Dog image for from card #36, and that was his dog in the card as well. David remembered, "The dog was named 'Cindy' and we all laughed about it afterwards because the Martian blew her to 'cinders!'"

Saunders was only paid $1.25 an hour to paint that incredible series, although Maurice Blumenfeld also contributed images. (After all the artworks were delivered, Saunders was hired to retouch the other artists' paintings so everything would look uniformly detailed and three dimensional, as he had done with other series in which he had been involved.) The bloody Mars Attacks lettering from the box and wrapper were also his work.

Saunders went on to work on many other classic sets, including Battle and Wacky Packages. The Wackys became Topps most sold item, even outselling their sports cards . By the 16 th series, Saunders had painted 478 of the 503 Wacky Packages (that's 95%!). Having made Topps millions, they finally agreed to pay him more than minimum wage. He was given a flat $50 fee per painting for the last batch of Wackys he painted... and Topps kept all the paintings. (The originals have since sold for thousands of dollars each.)

In 1980, Saunders was 73 and Topps asked him to paint a series called Weird Wheels. Although he was in failing health, he defied doctor's orders and agreed to paint what would be his final set. When his son questioned the wisdom of risking his health for a low paying job, he responded, "It's fun! I gotta keep working. What the hell else am I gonna do?"

Saunders lived until 1989, long enough to witness some appreciation from his fans. He became a celebrity at pulp and trading card shows, as well as paperback conferences and comics book conventions. Fan mail, visits by younger artists, and interviews proved to him that his work wasn't forgotten, and neither was he. As collectors, we can take some credit in making sure the work he thought was thrown away will last and be admired by future generations. David Saunders deserves even greater credit for creating this retrospective of Norm's work for similar reasons. If you're a Saunders fan, you should nab this book while you can, because only 5,000 were made to satisfy the hunger of countless fans. If you order it, do so from the publisher so David can earn back some of his inheritance sooner. Its $40, but well worth it. It has lots more information and over 880 priceless pictures. David also produced a very neat card set that parallels his book (which originally sold for just $10). Only 1,000 were made, and neither the cards nor books will be reprinted. So if you're a Norm Saunders fan, get them both while you can. They sure aren't making art like this anymore!

The web address is:

rev. 3.16.11