Weird Tales, Weird Cards!

By Kurt Kuersteiner © 2011 Monsterwax

Trading Cards

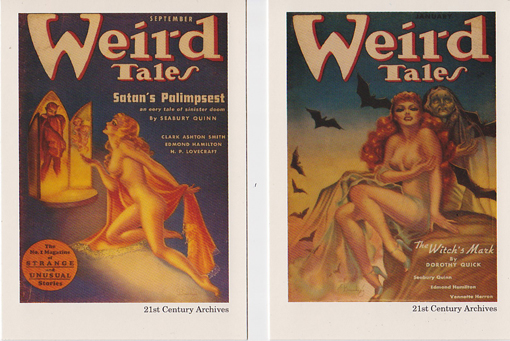

[Above: Beautiful examples of Brundage covers.]

Every time a New Year rolls around, a lot of television news programs do a “year in review” type show. They summarize events that happened in the last 365 days, in the mistaken belief that we have forgotten it from the first time it was reported. I’m more curious about older news, which seem “new” to me because I wasn’t around when it first happened. (In other words, history.) That’s one of the fun things about collecting cards. They often inform collectors about interesting but forgotten things that were common knowledge before our time.

A good example is the ground breaking magazine, Weird Tales. 2013 marks the 90th anniversary of the infamous pulp, which first began publication in 1923. It leaped off the newsstands in no small part because it often featured nude, sensual women on its covers. (That’s right, a roaring 1920’s horror magazine beat Playboy to the punch by three decades!) What happened beneath the covers was just as exciting. Weird Tales popularized a new genre, “Weird Fiction”, and gave a voice to some of the centuries newest and most influential writers, including H.P. Lovecraft, Robert E. Howard (“Conan the Barbarian”), Ray Bradbury, Clark Ashton Smith, Robert Bloch, and even the playwright, Tennessee Williams.

If you were in America during the 1920s, 30s, 40s, or 50s, it would have been difficult to avoid Weird Tales (unless you were in prison). Its seductive covers caught a lot of attention, not all of it positive, as they also caused it to be pulled from some of the more prudish newsstands. Despite this controversy-- or maybe because of it-- it became extremely well known and is still considered by many as the best fantasy magazine of all time.

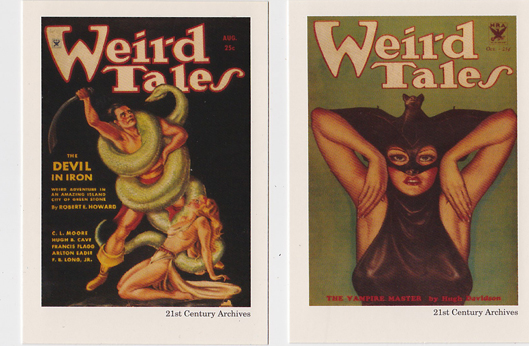

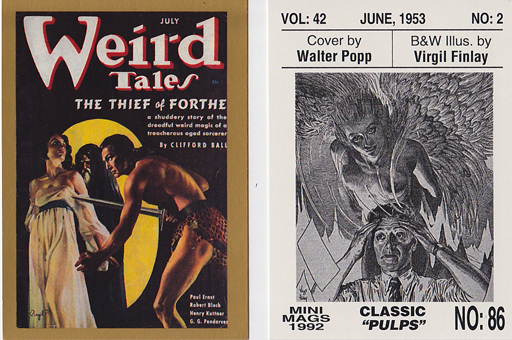

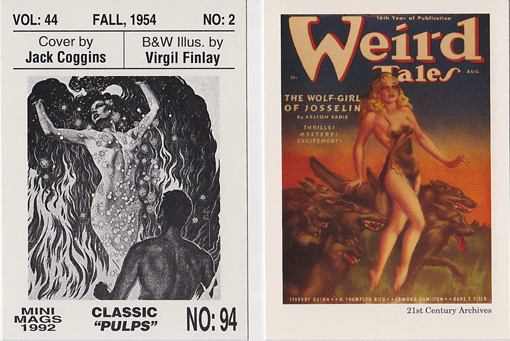

The main artist responsible for those captivating covers was a woman, Margaret Brundage. She was quite a pioneer in the profession, making history as the only successful female cover artist of the pulps. She had some stiff male competition too, including a young artist who started at Weird Tales: Virgil Finlay, considered by many to be one of the best illustrators of all time. His pen and ink drawings featured all sorts of elaborate stippling and cross hatching techniques, requiring far more time than regular line art, yet he still managed to crank out over 2,600 pieces in his 35 year career. Finlay contributed 19 covers (and interior illustrations for 62 issues), while Brundage did 66 covers. Another competitor at Weird Tales was Hannes Bok, who achieved his luminous lighting through an arduous glazing technique that he learned from his mentor, the master of ethereal light, Maxfield Parrish. Suffice it to say, Weird Tales had some eye grabbing art!

[Above: One of Virgil Finlay's 19 Weird Tales covers, and two of his 2,600 detail filled illustrations (from Sherry's Classic Pulps series). Compared those to the soft but sensual Brundage covers of a Wolf Girl]

Brundage worked in pastel chalks on illustration board. It gave her work a smooth beauty and a soft Technicolor glow. (It also made the editor careful not to sneeze around the originals.) Sadly, none of the cover artwork was ever returned to her and only a few exist to this day. However, collectors can still enjoy her artwork by collecting the magazines (which are now prized collectibles), or by acquiring the much cheaper set of trading cards released in 1993. Weird Tales was a 55-card set published by 21st Century Archives. They did a great job of writing about the magazine, the authors, and especially the artists.

Brundage’s history is well documented in the card set. She was married to a “former” hobo who avoided work and boozed it up with different women, leaving her home alone with their only child (a son). She had to earn the money to support the family and her invalid mother. She quickly realized that the editor preferred lots of exposed flesh on the cover, so she carefully read each upcoming story in search of potential opportunities to exploit his taste for eroticism. Sometimes, the racy covers had hardly anything to do with the actual plot. If even a dream or historical footnote made a sexy tangential mention, that was adequate enough! (Eventually, the authors followed suit and began to deliberately add such mentions to their stories so as to be chosen for the cover.)

Brundage had limitations however, and while beauty was her strength, the “beast” side of her art was weak. She was a former fashion designer and seemed incapable of drawing ugliness if her life (or livelihood) depended on it. Her covers always avoided monsters, and the few that featured “scary” characters appeared somewhat silly. Another limitation was muscles. She could draw a smooth woman’s form beautifully, but all her bare-chested men looked rather weak and fragile, like sissies. She compensated for this but hiding their bodies behind bushes, flames, or in one case, a giant coiled snake. The truth is, during the depression, she couldn’t afford to hire any models and used other illustrations for her reference. There just weren’t any body builders around to pose for her!

Readers never knew M. Brundage was a woman until Halloween 1934. Once they realized there was a lady beneath the mask, it made many uncomfortable with her nude art. It became a recurring debate in the letters to the editor. Another gender-bender comedy of errors occurred after the magazine published an exciting story by C.L. Moore. Henry Kuttner, a fellow Weird Tales writer, wrote Moore a fan letter, but was shocked to discover C.L. was a she. He must have recovered, though. They married four years later.

There are many interesting details about Weird Tales. One of its most famous writers was H.P. Lovecraft, who was actually invited to become its editor in 1924, but declined saying he was too old to move to Chicago at the ripe old age of 34! The magazine continued to publish his stories, but foolishly shied away from his longer masterworks, including The Shadow Over Innsmouth, and At The Mountains of Madness. (The latter novella went on to be serialized and helped siphon off readers to a competing magazine, Astounding Stories.) Lovecraft should have taken the WT editor job. He married that same year and moved from Providence anyway (to New York city), but it ended in divorce due to his wife losing her hat shop and he not being able to find work. He returned home and died 13 years later, poor and malnourished.

Brundage’s career at Weird Tales all but ended in 1938 when the company moved to New York. Her delicate chalk covers couldn’t survive the trip through the mail to get there. She contributed a few that were painted, but they couldn’t measure up to her phenomenal pastel covers. Nor did it help that the company cut their $90 cover payment to just $50. (Finley resigned in protest, but Hannes Bok stayed on for a while.) Brundage died in poverty in 1976 at age 76, forgotten by all but a few loyal fans.

The era of the pulps came to a close mid century. Like the other pulps, WT suffered from a newsprint shortage during WW2. It was hurt more after the war due to increased competition from comic books, radio drama, and “free” TV. (All were entertainment that required less reading.) WT lasted longer than most, closing shop in 1954 after 31 years and 279 issues. It made several valiant attempts to reboot, especially in 1988, but it went into debt and was resold in 2000, and 2005, and again in 2011. It ran afoul the PC police recently when it announced plans to run Victoria Foyt’s sci-fi story “Save the Pearls” (which dealt with reverse discrimination and climate change). The once bold magazine was forced to ban the story to appease activists and avoid boycotts.